Property Tax Visualization Tool

Sources of Local General Revenue

Select States to Compare

Select one or more states on the map or from the list of states to compare key property tax data below. Charts and tables will update automatically.

Select States

2025 United States

Local governments are highly reliant on the property tax in the United States; in 2022, property tax revenues made up 28.9 percent of local general revenue, second only to state aid (figure U.S.-1). However, reliance on the property tax varies markedly across the country. In New England, local governments rely heavily on the property tax, with local governments in five of the six New England states (Connecticut, Massachusetts, Maine, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island) deriving 50 percent or more of their general revenues from the property tax (Significant Features of the Property Tax). In contrast, local governments in the East South Central region (Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Tennessee) rely on property taxes for no more than 24 percent of their general revenues, lower than the U.S. average. See Sources of Local General Revenue

Property tax systems across the United States differ along many dimensions, as described in later sections of this narrative. Additionally, two states are notable for having two distinct property tax systems within their respective borders. In Illinois, Cook County’s property tax structure differs from that used in the rest of the state; similarly, New York City has its own property tax system, separate from that of New York State (Lincoln Institute of Land Policy and Minnesota Center for Fiscal Excellence 2024).

The language used to describe features of state and local property tax systems also often varies from state to state. For example, Indiana calls its rate limit (1 to 3 percent of assessed value) a circuit breaker, while in most other states, the term circuit breaker is reserved for residential property tax relief programs under which property tax relief increases as household income falls (Bowman et al. 2009).

Property Tax Reliance

State and local property tax burden measured as property tax per capita ranged from $697 in Alabama to $4,334 in the District of Columbia in 2022. Property tax revenue accounted for about 14.3 percent of state and local revenue nationally; however, the share of revenue varied by state from 6 percent in Alabama to 34 percent in New Hampshire. Property tax revenue is derived from residential, business, rental, and farm property. The effective tax rate on a median-value owner-occupied home ranged from 0.3 percent in Hawaii to 2.7 percent in New Jersey (Significant Features of the Property Tax). See Selected Property Tax Statistics

Administration And Assessment

In the vast majority of states, assessment is primarily the responsibility of counties. However, in other states, assessments may be carried out either centrally by the state, as in Maryland and Montana, or may be a function of municipal governments such as cities and towns, as in Connecticut. See Property Tax Features

Not every state levies property taxes on 100 percent of a property’s market value. In New Mexico, for example, taxable value is defined as 33 1/3 percent of market value, so the taxable value of a home with a market value of $300,000 is $100,000. Similarly, assessed value is not always based on market value. For example, in California, assessed values are based on the price paid when the property was purchased, allowing only limited increases in assessments afterward.

Limits On Property Taxation

States have imposed legal limits on property taxation since at least the 1850s (Paquin 2024). In 2024, 45 states and the District of Columbia restricted property taxation either through limits on rates, limits on levies, limits on growth in assessed values, or some combination. In 2024, limits on property tax rates, the oldest and most widespread type of limit, existed in 36 states, and 33 states plus the District of Columbia had limits on property tax levies, while 19 states restricted growth in property values through assessment limits (Paquin 2024; Significant Features of the Property Tax).

Property Tax Relief And Incentives

Circuit breaker property tax relief programs provide income-targeted residential property tax relief that declines as income rises. Many states restrict these programs to elderly homeowners; although in some places, homeowners and renters of all ages may qualify (Bowman et al. 2009). In 2023, 29 states and the District of Columbia authorized property tax circuit breaker programs (Significant Features of the Property Tax).

Property tax deferral programs allow burdened homeowners to defer property tax payments while they own the home, with the deferred taxes and interest payable upon transfer of ownership. These programs, usually limited to seniors with low income, allow qualifying homeowners to remain in their homes using their home equity to secure their property tax obligations. Statewide deferral programs were available in 21 states and the District of Columbia in 2023, but utilization is low. In another 11 states, local governments have the option to offer deferrals (Langley and Youngman 2021; Significant Features of the Property Tax).

State property tax incentives for economic development generally fall into five categories: abatement programs, firm-specific incentives, tax increment financing (TIF), enterprise zone programs, and tax-exempt industrial development bonds combined with property tax exemption and sometimes payments in lieu of taxes. TIF is the most common economic property tax incentive for business, but recent research finds, in many cases, it has failed to promote economic development (Merriman 2018). The use of business tax incentives has increased markedly in the last 50 years. They now exist in all 50 states and the District of Columbia in one form or another (Kenyon, Langley, and Paquin 2024; Significant Features of the Property Tax).

Key Property Tax History

The federal government briefly imposed a temporary tax on property a few times, first in 1798 to generate funds for national defense, and most recently in 1861 to pay for the Civil War (Larkin 1988; Wallis 2001). Once a major revenue source for state governments, the property tax is now a minuscule source for most states (Minnesota Center for Fiscal Excellence 2020). Seven states have used state-levied property taxes for school funding (Alabama, Kansas, Michigan, Montana, Minnesota, Vermont, and Washington) (Haveman 2020). However, the property tax has endured throughout U.S. history as the chief revenue source for local governments.

After independence, all states taxed property to some extent. However, when in 1790 the federal government assumed state debt, state reliance on property taxation declined, with a handful of states eliminating property taxes entirely. State property tax reliance increased briefly due to the War of 1812 but afterward declined through the 1830s, then remained fairly constant until 1900 (Wallis 2001).

Local governments, which had continued to rely heavily on property taxes, grew rapidly relative to the national and state governments from 1840 through the beginning of the 20th century (Wallis 2001). It was during this period that states began to enact limits on property taxation, generally capping property tax rates for certain local governments (Paquin 2024). In 1902, the year of the first comprehensive census of governments, the property tax was the most important revenue source for state and local governments in the United States, generating 68 percent of combined state and local revenue.

Between 1900 and 1942, the property tax again diminished as a state revenue source as state governments shifted away from the property tax in favor of sales and income taxes. Local governments in this period generated about 70 percent of their revenues from property taxes (Wallis 2001). Tax protests grew out of the Great Depression and led states to enact additional limits on property taxation, including caps on growth in tax levies (Paquin 2024).

California’s passage of Proposition 13 in 1978 led to the most significant property tax limitation movement to date (Paquin 2024). In the five years following its passage, states considered more than 58 ballot measures to limit the property tax. Following California’s lead, states began to enact increasingly stringent tax limitations, including, for the first time in history, broad limits on increases in assessments (Paquin 2024; Youngman 2016).

Historically, the property tax has been closely linked to education, providing the largest source of local education funding (Kenyon 2007; Kenyon, Paquin, and Reschovsky 2022; McGuire, Papke, and Reschovsky 2015). Although the property tax, by virtue of its immobile base, has provided a stable funding source for schools, inequities among school districts have been the subject of legal challenges across the United States since the 1960s and have led to massive restructuring of many states’ property tax systems (Kenyon, Paquin, and Munteanu 2024).

One of the most contentious property tax issues in recent years has involved the valuation of “big box” retail stores. These cases have dealt with a range of issues, including the appropriate treatment of property with special value to its current owner, the effect of a lease on the valuation of the underlying fee interest, and the analysis of owner-imposed deed restrictions on future use. In particular, the appropriate use of vacant or “dark” properties as comparables for the valuation of successfully functioning stores has led to these being termed “dark store” cases. Legal challenges have seen widely differing outcomes in these cases. The Michigan Tax Tribunal was an early leader in approving dramatic reductions in “big box” assessments. Together with the state’s limitation on annual increases in taxable value, these resulted in the loss of over $100 million in local tax revenue. A 2016 Michigan Court of Appeals decision was thought by many to signal a potential change by finding the tribunal to be in error when it failed to account for the effect of owner-imposed restrictions on future use of comparable properties (Menard, Inc. v. City of Escanaba, 2016). However, in 2022 the court of appeals upheld the tribunal’s decision to reduce Menard’s assessment by half in that case, and took the same approach in a later Walmart challenge (Menard, Inc. v. City of Escanaba, 2022; Walmart Real Estate Business Trust v. City of Bad Axe, 2022). At the same time, a 2022 decision by the Kansas Supreme Court unanimously rejected valuations of Walmart and Sam’s Club stores based on vacant or “dark” comparable sales, and in 2023 the Wisconsin Supreme Court rejected the use of abandoned and distressed properties as comparables for successful stores (In re Equalization Appeals of Walmart Stores, Inc., 2022; Lowe’s Home Centers, LLC v. City of Delavan, 2023). Although most efforts to address these controversies through state legislation have been unsuccessful, a Maine enactment required consideration of all methods of valuation and limited the use of restricted properties as comparable sales (Murphy 2022).

Recent Developments

In 2022, state and local governments raised $649 billion through the property tax, which accounted for 28.9 percent of local general revenue and 0.7 percent of state general revenue (Significant Features of the Property Tax).

In December 2017, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) was enacted, the first major overhaul of the federal tax code since 1986. This tax act impacted property taxation in two important ways. First, the federal government capped the allowable deduction of state and local income, sales, and property taxes (SALT) at $10,000 per year. Several states attempted to enact workarounds, most of which were thwarted by new IRS rules. Four states sued the federal government claiming it violated state sovereignty, but a federal judge dismissed the lawsuit in 2019 (Reitmeyer 2019) and the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear the case in 2022 (Muse 2022). In 2020, the IRS cleared the way for some workarounds by allowing pass-through businesses (non-C corporations) to opt to pay taxes at the entity level (Walczak 2020). By 2025, 36 states had enacted entity-level taxes in response to the SALT deduction cap enacted in 2017 (Multistate Tax Commission). These state laws allow pass-through businesses to choose to pay taxes at the entity level rather than passing the tax liability to their owners. The entity can deduct the value of property taxes paid from its federal taxes as a business expense and then the partners would get a credit for taxes paid, to offset personal tax liability. The second way the TCJA impacted federal tax deductibility of property taxes was the near doubling of the standard deduction, which significantly reduced the percentage of federal taxpayers who itemized deductions. Both TCJA changes may make it more difficult for state and local governments to raise property taxes (Tannenwald 2018; Tax Policy Center 2018). In 2025, as part of the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act,” the SALT deduction cap increased from $10,000 to $40,000 starting in tax year 2025, with an annual 1 percent increase from 2026 through 2029. The cap is scheduled to revert to $10,000 in 2030 (Dore 2025).

Prior to a landmark U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Tyler v. Hennepin County in 2023, about a dozen states authorized governments to take absolute title to properties through property tax foreclosure without refunding the excess sale proceeds to the former owner. In recent years, the Pacific Legal Foundation (PLF) has represented plaintiffs challenging this practice in states across the country including Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, and Nebraska. In 2023, a Minnesota plaintiff represented by the PLF won a unanimous verdict on takings grounds in the U.S. Supreme Court in Tyler v. Hennepin County (2023) (Liptak). Since the ruling, Arizona (Senate Bill 1431 of 2024), Colorado (House Bill 24-1056 of 2024), Idaho (House Bill 444 of 2024), Louisiana (Amendment 4 of 2024), Maine (Legislative Document 101 of 2023), Massachusetts (Chapter 140 of the Acts of 2024; House Bill 4801 of 2024), Minnesota (House File 5246 of 2024), Nebraska (Legislative Bill 727 of 2023), New Jersey (Assembly Bill 3772 of 2024), Oregon (House Bill 4056 of 2024), and South Dakota (House Bill 1090 of 2024) have enacted legislation to facilitate the refund of surplus from the sale to the delinquent taxpayer.

The Covid-19 pandemic had an uneven effect on state and local government revenues. Initially, states saw steep declines in tax revenues, but for most governments tax collections fell less than projected (with some revenues shifting from one tax year to the next) and started to recover sooner than expected. By February 2021, 29 states had raised as much or more tax revenue in the first 12 months of the pandemic as they had in the 12 months prior to the pandemic (Rosewicz, Theal, and Fall 2021). In response to concerns about taxpayers’ abilities to keep up with property tax payments, state and local governments across the United States adopted one-time policies, most commonly extending property tax due dates or deferring interest and penalties for late payments (Ryan 2020). Record growth in state revenues in 2021 and 2022, and infusions of federal stimulus funds, fueled large surpluses, leading to higher spending and tax cuts. Several states cut property taxes, and others, such as Maine, Nebraska, and Oregon, created or expanded property tax relief programs (National Association of State Budget Officers 2023).

State rainy day funds swelled in the post-pandemic period—the median state rainy day fund balance climbed 31 percent in 2023 alone. However, growth in rainy day funds slowed in fiscal year 2024, returning to more typical levels (Pew 2025). Many states also experienced slower revenue growth in fiscal year 2024, and as federal pandemic aid programs and funding expired at the end of 2024, some states grappled with funding gaps. According to an analysis by Pew, “state budget stresses are more widespread than they have been at any time since at least 2020,” affecting even states with strong recent fiscal records (Goodman 2025). Many states were projecting structural deficits, with forecasts indicating that recurring revenues may consistently fall short of ongoing expenditures following recent tax cuts and spending increases (Goodman 2025). Pew projected that while states would continue to consider property tax cuts in 2025, those reductions would often be paired with increases to other taxes to offset the revenue loss (Goodman 2025).

The pandemic accelerated a shift toward remote work, reducing demand for commercial office property, particularly in cities (Ramani and Bloom 2021). Declining commercial property values along with rapidly appreciating home values can present local tax challenges. Some major cities have projected a downward shift in commercial property tax revenue (Brosy 2023; Chernick, Copeland, and Merriman 2021). A recent study of 47 large cities examined how post-pandemic declines in office building values could affect local budgets. For the 13 cities with the largest office markets, the median projected decline in commercial property tax revenue by 2031 ranges from 2.5 to 3.5 percent or from or from 0.9 to 3.2 percent of total city revenue depending on the predictions in the forecast. The severity of the fiscal impact varied with cities more reliant on commercial property tax revenue, such as Boston and Dallas, being particularly vulnerable (Brosy et al. 2024).

In contrast to the decline in the commercial property sector, U.S. residential property values rose to record highs during and after the Covid-19 pandemic. Between January 2020 and July 2024, aggregate U.S. home prices rose 54.4 percent in nominal terms (26.7 percent when adjusted for inflation), far outpacing income growth and inflation over the same period (Walczak 2024). From early 2020 to mid-2022, prices climbed as much as 45 percent (24 percent, inflation-adjusted) (Brosy and Langley 2025). As these gains led to increased assessed values, homeowners expressed concern about potential spikes in their property tax bills. While national median property tax payments rose 2 percent from 2020 to mid-2024 (adjusted for inflation), the extent of property tax increases varied widely across states, depending on features of each state’s property tax system such as the design of property tax limits and the degree to which local governments reduced tax rates to mitigate property tax growth amid rapidly rising home prices (Brosy and Langley 2025).

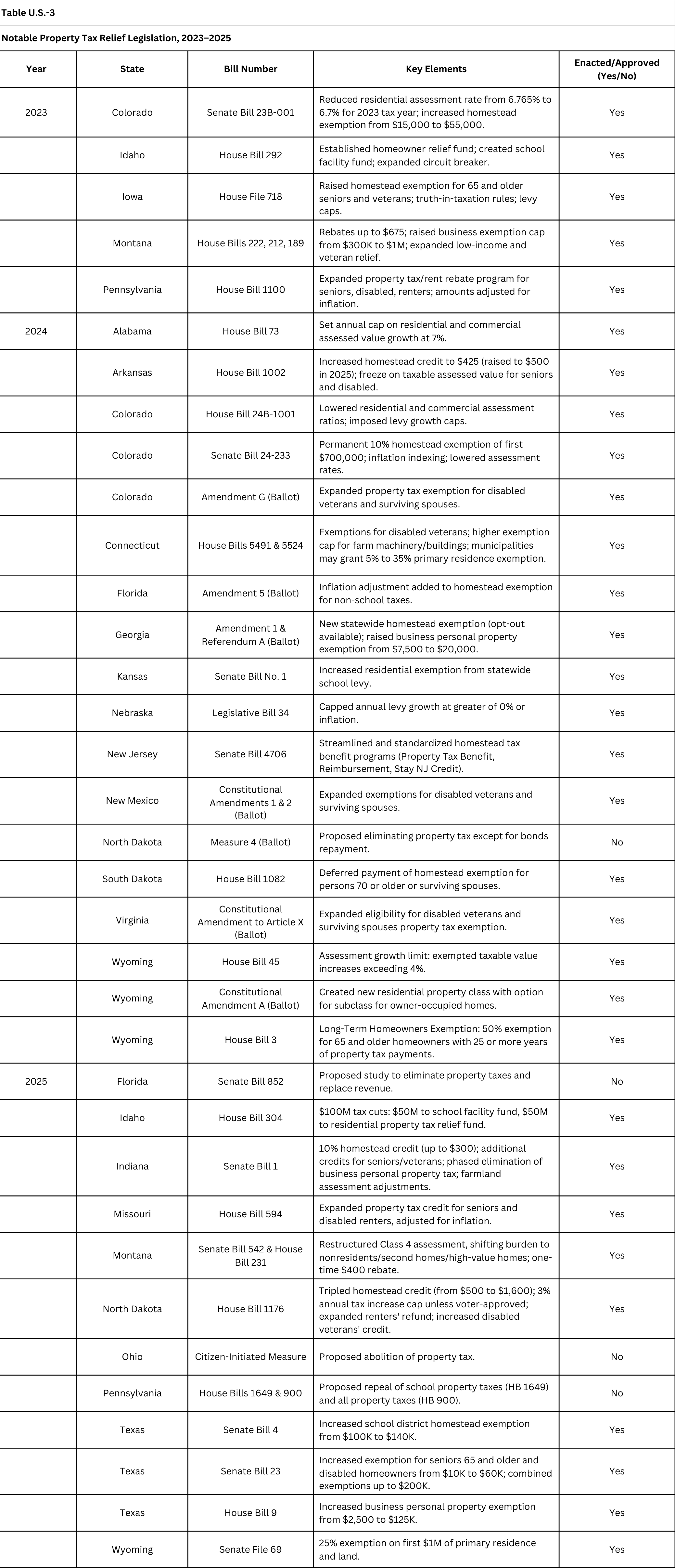

In recent years, many states have proposed or enacted property tax relief measures to address homeowners' concerns about rising property tax bills (table U.S.-3). Legislative action in 2023 included enactments in Colorado, Idaho, Iowa, Montana, and Pennsylvania, which introduced various relief measures such as assessment rate reductions, homestead exemption expansions, and rebate programs.

In 2024, several states, including Arkansas, Colorado, Connecticut, Kansas, New Jersey, and South Dakota, passed legislation enhancing homestead exemptions, while multiple states (Colorado, New Mexico, and Virginia) approved ballot measures expanding exemptions for disabled veterans and their surviving spouses. North Dakota also engaged in a high-profile campaign to abolish property taxes entirely, but the ballot measure ultimately failed.

Property tax relief remained a major focus through 2025, with states such as Idaho, Indiana, Missouri, Montana, North Dakota, Texas, and Wyoming enacting substantial measures, including caps on tax increases and credits for homeowners and veterans. Meanwhile, attempts to repeal property taxes in Florida, Ohio, and Pennsylvania did not advance. Additionally, five states imposed or amended tax limits during 2023 and 2024 to counteract sharp increases in assessed property values, reflecting a continuing legislative focus on easing the property tax burden.

Sources

Auxier, Richard C. 2023. “Reviewing Three Years of State Tax Cuts.” Tax Policy Center. (July 20). https://taxpolicycenter.org/taxvox/three-years-state-tax-cuts.

Bahl, Andrew. 2022. “In Major Decision, Kansas Supreme Court Rules Against Walmart, Sam's Club in Property Tax Dispute.” Topeka Capital-Journal, July 1. www.cjonline.com/story/news/state/2022/07/01/kansas-supreme-court-rules-against-walmart-sams-club-property-taxes-retail/7786207001/.

Ballotpedia. “North Dakota Initiated Measure 4, Prohibit Taxes on Assessed Value of Real Property Initiative (2024).” https://ballotpedia.org/North_Dakota_Initiated_Measure_4,_Prohibit_Taxes_on_Assessed_Value_of_Real_Property_Initiative_(2024).

BeMiller, Haley. 2025. “No More Property Taxes? Ohio Group Pitches Amendment to Get Rid of Them.” Columbus Dispatch, May 2. https://www.dispatch.com/story/news/politics/2025/05/02/ohio-group-proposes-amendment-to-eliminate-property-taxes/83406569007/.

Bowman, John H., Daphne A. Kenyon, Adam Langley, and Bethany Paquin. 2009. Property Tax Circuit Breakers: Fair and Cost-Effective Relief for Taxpayers. Policy Focus Report. Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. www.lincolninst.edu/publications/policy-focus-reports/property-tax-circuit-breakers.

Brosy, Thomas. 2023. “The Future of Commercial Real Estate and Big City Budgets.” Tax Policy Center. (August 22). www.taxpolicycenter.org/taxvox/future-commercial-real-estate-and-big-city-budgets.

Brosy, Thomas, Richard C. Auxier, Nikhita Airi, Gabriella Garriga, and Muskan Jha. 2024. “The Future of Commercial Real Estate and City Budgets.” Tax Policy Center. (May 1). https://taxpolicycenter.org/publications/future-commercial-real-estate-and-city-budgets.

Brosy, Thomas, and Adam H. Langley. 2025. “When Property Values Rise, Do Property Taxes Rise Too?” Policy Download. Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. (February). https://www.lincolninst.edu/publications/policy-downloads/property-values-rise-property-taxes-rise-too/.

Chernick, Howard, David Copeland, and David Merriman. 2021. “The Impact of Work from Home on Commercial Property Values and the Property Tax in U.S. Cities.” Policy Brief. Washington, DC: Institute of Tax and Economic Policy. (November). https://itep.sfo2.digitaloceanspaces.com/2021101_PropertyTaxReport.pdf.

Dore, Kate. 2025. “Trump’s ‘Big Beautiful Bill’ Passes SALT Deduction Limit of $40,000. Here’s Who Benefits.” CNBC. July 3. https://www.cnbc.com/2025/07/03/trumps-big-beautiful-bill-salt-deduction.html.

Garcia-Milà, Theresa, Therese J. McGuire, and Wallace E. Oates. 2014. “Strength in Diversity? Fiscal Federalism Among the Fifty U.S. States.” Working paper No. 1001. Barcelona, Spain: Barcelona Graduate School of Economics. https://bw.bse.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/1001-file.pdf.

Garofalo, Pat. 2022. “Maine Took On Big-Box Stores ... And Won.” Fair and Equitable (20)5: 12–13. https://researchexchange.iaao.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?filename=2&article=1022&context=f-e&type=additional.

Goodman, Josh. 2025. “Lawmakers Face Budget Crunches, Tough Decisions to Close Expected Shortfalls.” Pew. (January 13). https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2025/01/13/lawmakers-face-budget-crunches-tough-decisions-to-close-expected-shortfalls.

Hamilton, Billy 2024. “An Intermezzo Year in State Tax Policy.” Tax Notes State. December 23. https://www.taxnotes.com/tax-notes-state/budgets/intermezzo-year-state-tax-policy/2024/12/23/7p5kf.

———. 2025. “The Year of the Property Tax.” Tax Notes State. June 2. https://www.taxnotes.com/tax-notes-state/property-taxation/year-property-tax/2025/06/02/7s7nv.

Haveman, Mark. 2020. “Time to Reassess the State Property Tax.” Minnesota Center for Fiscal Excellence.

Ingles, Jo 2025. “Amendment to Abolish Property Taxes in Ohio Won't Be on the Fall Ballot This Year.” Statehouse New Bureau. June 26. https://www.statenews.org/government-politics/2025-06-26/amendment-to-abolish-property-taxes-in-ohio-wont-be-on-the-fall-ballot-this-year.

International Association of Assessing Officers Special Committee on Big-Box Valuation. 2018. “Commercial Big-Box Retail: A Guide to Market-Based Valuation.” 15(1): 47–67. (September). https://researchexchange.iaao.org/jptaa/vol15/iss1/3/.

Jimenez, Andrea, and Mandy Rafool. 2024. “Voters in These States Will Decide on Tax Issues.” National Conference of State Legislators. (October 22). https://www.ncsl.org/state-legislatures-news/details/voters-in-these-states-will-decide-on-tax-issues.

Kenyon, Daphne A. 2007. The Property Tax–School Funding Dilemma. Policy Focus Report. Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. (December). www.lincolninst.edu/publications/policy-focus-reports/property-tax-school-funding-dilemma.

Kenyon, Daphne A., Adam H. Langley, and Bethany P. Paquin. 2012. Rethinking Property Tax Incentives for Business. Policy Focus Report. Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. (June). www.lincolninst.edu/publications/policy-focus-reports/rethinking-property-tax-incentives-business.

Kenyon, Daphne A., Bethany Paquin, and Andrew Reschovsky. 2022. Rethinking the Property Tax-School Funding Dilemma. Policy Focus Report. Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. (November). www.lincolninst.edu/publications/policy-focus-reports/rethinking-property-tax-school-funding-dilemma.

Kenyon, Daphne A., Bethany Paquin, and Semida Munteanu. 2024. “School Funding Litigation.” Working paper No. WP24DK1. Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. (July). https://www.lincolninst.edu/publications/working-papers/school-funding-litigation/.

Langley, Adam H., and Joan Youngman. 2021. Property Tax Relief for Homeowners. Policy Focus Report. Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. www.lincolninst.edu/publications/policy-focus-reports/property-tax-relief-homeowners.

Larkin, Jack. 1988. The Reshaping of Everyday Life: 1790-1840. New York: Harper Perennial.

Lincoln Institute for Public Policy and Minnesota Center for Fiscal Excellence. 2024. 50-State Property Tax Comparison Study: For Taxes Paid in 2023. (July). https://www.lincolninst.edu/publications/other/50-state-property-tax-comparison-study-2023/.

Liptak, Adam. 2023. “States Are Not Entitled to Windfalls in Tax Disputes, Supreme Court Rules.” New York Times, May 25. www.nytimes.com/2023/05/25/us/supreme-court-condo-taxes.html.

McGuire, Therese J., Leslie E. Papke, and Andrew Reschovsky. 2015. “Local Funding of Schools: The Property Tax and Its Alternatives.” In Handbook of Research in Education Finance and Policy, Second Edition, ed. Helen F. Ladd and Margaret E. Goertz. New York, NY: Routledge.

Merriman, David. 2018. Improving Tax Increment Financing (TIF) for Economic Development. Policy Focus Report. Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. (September). www.lincolninst.edu/publications/policy-focus-reports/improving-tax-increment-financing-tif-economic-development.

Minnesota Center for Fiscal Excellence. 2020. “Property Taxes Imposed by States: A National Comparison.”

Multistate Tax Commission. “State Pass-Through Entity (PTE) Taxes.” https://www.mtc.gov/uniformity/project-on-state-taxation-of-partnerships/state-pass-through-entity-pte-taxes/.

Murphy, Edward D. 2022. “Legislature Moving to Curb ‘Dark Store Theory’ Tax Assessments.” Portland Press Herald, March 14. https://www.pressherald.com/2022/03/14/legislature-moving-to-curb-dark-store-theory-tax-assessments/.

Muse, Andrea. 2022. “U.S. Supreme Court Rejects States’ SALT Cap Suit.” Tax Notes State. April 25. https://www.taxnotes.com/tax-notes-state/exemptions-and-deductions/us-supreme-court-rejects-states-salt-cap-suit/2022/04/25/7ddcq.

———. 2023. “Wisconsin High Court Upholds ‘Dark Stores’ Exclusion in Lowe's Valuation.” State Tax Notes. February 27. www.taxnotes.com/tax-notes-state/appraisals-and-valuations/wisconsin-high-court-upholds-dark-stores-exclusion-lowes-valuation/2023/02/27/7fz68.

National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO). 2023. “The Fiscal Survey of States.” (Spring). https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/NASBO/9d2d2db1-c943-4f1b-b750-0fca152d64c2/UploadedImages/Fiscal%20Survey/NASBO_Spring_2023_Fiscal_Survey_of_States_S.pdf.

North Dakota Office of the Secretary of State. 2024. ”Analyses of the Statewide Measures Appearing on the Election Ballot: November 5, 2024.” https://www.sos.nd.gov/sites/www/files/documents/elections/measures/analyses-2024-general-measure4.pdf.

Paquin, Bethany P. 2015. “State-Imposed Property Tax Limitations: Trends and Outlook.” State Tax Notes (August 24): 711–716.

Paquin, Bethany P. 2024. “Chronicle of the 172-Year History of State-Imposed Property Tax Limitations.” Working paper No. WP25SBP1. Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. https://www.lincolninst.edu/publications/working-papers/chronicle-172-year-history-state-imposed-property-tax-limitations/.

Ramani, Arjun, and Nicholas Bloom. 2021. “The Donut Effect of Covid-19 on Cities.” Working paper 28876. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. (May, revised December 2022). www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w28876/w28876.pdf.

Reitmeyer, John. 2019. “Judge Rules Against NJ, Other States in Case Against Federal SALT Cap.” NJ Spotlight News, October 1. https://www.njspotlight.com/2019/10/judge-rules-against-nj-other-states-in-case-against-federal-salt-cap.

Roberts, May. 2023. “Understanding 2023 Property Tax Relief.” Idaho Center for Fiscal Policy. (May 5). https://idahofiscal.org/understanding-2023-property-tax-relief/.

Rosewicz, Barb, Justin Theal, and Alexandre Fall. 2021. “State Tax Revenue Passes a Recovery Milestone.” Pew. (May 7). https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2021/05/07/state-tax-revenue-passes-a-recovery-milestone.

Ryan. 2020. “COVID-19: Pandemic Impact on Property Taxes.”

Smith, Brandon. 2025. “Senate Gives Final Approval to Major Property Tax Reform Bill, Sends It to Governor.” WNIN. April 14. https://news.wnin.org/2025-04-14/senate-gives-final-approval-to-major-property-tax-reform-bill-sends-it-to-governor.

Significant Features of the Property Tax. https://www.lincolninst.edu/data/significant-features-property-tax/. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy and George Washington Institute of Public Policy.

Tannenwald, Robert. 2018. “Tax Issues from 2017 and to Look for in 2018.” State Tax Notes. January 22.

https://taxfoundation.org/research/state-tax/property-tax-relief/.

Tax Policy Center. 2018. “T18-0002 - Impact on the Number of Itemizers of H.R.1, The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), By Expanded Cash Income Percentile, 2018.” (January 11). www.taxpolicycenter.org/model-estimates/impact-itemized-deductions-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act-jan-2018/t18-0002-impact-number.

Theal, Justin. 2025. “State Rainy Day Fund Growth Slowed in Fiscal 2024.” Pew. (Updated March 27). https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/data-visualizations/2014/fiscal-50/reserves-and-balances.

Wahrmund, Kennedy. 2025. “Texas Governor Signs Property Tax Relief Package.” Tax Notes State. June 18. https://www.taxnotes.com/tax-notes-today-state/exemptions-and-deductions/texas-governor-signs-property-tax-relief-package/2025/06/18/7sk3h.

Walczak, Jared. 2020. “IRS Signals Approval of Entity-Level SALT Cap Workaround, But States Should Still Think Twice.” Tax Foundation. (November 11). https://taxfoundation.org/irs-salt-cap-workaround.

———. 2024. “Confronting the New Property Tax Revolt.” Tax Foundation. (November 5). https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/state/property-tax-relief-reform-options/.

Wallis, John Joseph. 2001. “A History of the Property Tax in America.” In Property Taxation and Local Government Finance, ed. Wallace E. Oates. Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Wilson, Sara. 2023. “Colorado Lawmakers Pass Property Tax Relief as Special Session Wraps Up." Colorado Newsline. November 21. https://coloradonewsline.com/2023/11/21/colorado-property-tax-relief/.

Youngman, Joan. 2016. A Good Tax: Legal and Policy Issues for the Property Tax in the United States. Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. www.lincolninst.edu/publications/books/good-tax.